An active campaign is underway calling for an upgrade to the A10 between Cambridge and King’s Lynn via Ely. At the centre are Conservative Party county councillors who claim the A10 is unfit for purpose and that “doing nothing is not an option”.

The campaign is wrong headed. Kings Lynn to Cambridge is not a strategic corridor and it makes no sense to try and make it into one. Turning congested sections of the road into motorways can only ever be a short term fix which experience shows will soon fill up with more cars. Instead, the emphasis should be on making the road safer, and on giving people easier, quicker and better ways of getting around.

What is the problem with the A10?

The A10 between Cambridge and Kings Lynn forms at least three distinct sections. Cambridge to Ely is important for commuting and leisure and suffers peak-time congestion. Between Ely and Downham Market the road is more lightly used, but there are some safety concerns. Finally, between Downham Market and Kings Lynn the road bisects a number of settlements causing severance, pollution and environmental issues. This section is in Norfolk, rather than Cambridgeshire.

In sum, there are no common problems to address, the road isn’t a strategic link for a sizeable chunk of its route, and half of it is in a neighbouring county.

So, what’s going on? There are three potential reasons why the upgrade proposal might have appeared now:

1. Political – In sight of an election, this is an attempt to find an important sounding project to campaign for. East Cambridgeshire councillors have a particular attachment to new roads, having campaigned for bypasses of Ely and Fordham in recent years.

2. Economic – The proponents might genuinely believe there is a case for spending large sums trying to create a strategic road link between Kings Lynn and Cambridge. Even with Cambridge’s growing influence, this is implausible and the existing electrified rail link provides sufficient capacity and much shorter journey times than the A10 even if it were expanded.

3. Local – There are long-held ambitions to dual sections between Ely and Cambridge. Attaching this dream it to a wider proposal might be an attempt to give it more credibility.

While the economic case for a strategic route is likely to be very weak, the first and third points combined may mean the proposal ends up being given serious consideration.

What are they thinking of?

At this stage, no plans have been announced concerning the A10. Instead, county council work is apparently underway looking at options for ‘upgrading’ the road. This in itself is frustrating. As other areas of the country have found out to their cost, little or no public input at the initial stage can mean a fait accompli of options then coming forward.

‘Upgrade’ covers a range of interventions. Highways England uses ‘upgrades’ to describe anything from a new dual carriageway and road widening projects to junction, roundabout and safety improvements. It is reasonable to expect ‘upgrading’ the A10 to cover the same territory, meaning it will look at straightening sections of the road, reworking junctions, and dualling at least some parts, for example between Waterbeach and Cambridge. The question is whether any of it would be justified or effective.

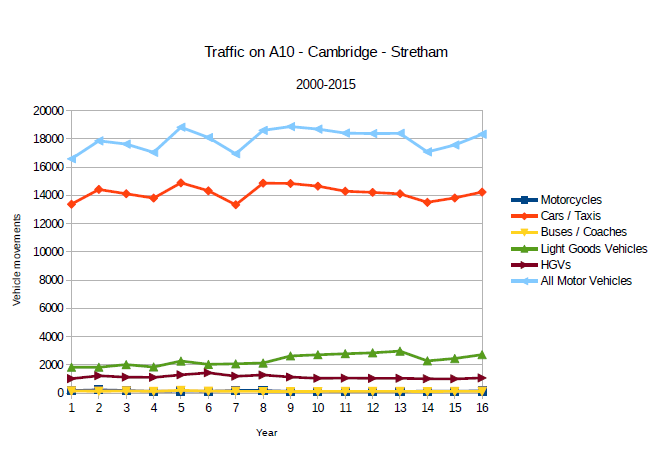

At peak times, the A10 from Cambridge to Ely is certainly a busy section of road. The graph below shows traffic on the road over the 9 miles stretch between Cambridge and Stretham (the section for which statistics are available) over a 15 year period.

There was a 10 per cent growth in traffic from 2000 to 2015 but beneath this, there are few consistent trends in traffic:

-

Most recent traffic stats are below that of the peak period (2007 – 2011)

-

While cars and taxis make up the large majority of vehicle movements, the most recent data (2015), shows fewer cars and taxis using this section of road than, for example, in 2001.

-

HGV traffic has increased by 5 per cent and from a relatively low base

-

But bus and coach traffic has collapsed by nearly a fifth (19 per cent)

-

There has been significant growth in the number of light goods vehicle movements. These represented only 10 per cent of overall traffic in 2000, but their subsequent growth accounts for half (49 per cent) of the total increase in traffic on this section of road.

So, there is some traffic growth but the picture is fluctuating and complex one. What about the future? Surely the area’s fast growing population demands that the road be expanded?

Traffic and population

Between 2000 and 2015, both East Cambridgeshire and South Cambridgeshire saw their populations rise by over 20 per cent – twice as fast as total traffic on the A10 and four times faster car traffic. Even accepting an increase in rat-running on parallel minor roads, population is rising much faster than traffic.

There are three reasons for this. First, the way people work and commute is changing. There are now over 8 million people working part time and large numbers regularly working from home for all or some of their employed hours. The days of 9 to 5 office hours are also on the wane, with less traditional shift patterns a feature of many roles in the service sector. All these contribute to a shift away from travel at busiest times and towards a more efficient use of road capacity.

Second, people are shifting to other modes. Over the same period (2000/01 – 2015/16), use of Ely railway station increased by 274 per cent and the station now serves an estimated 2.1m entries and exits each year. Use of Waterbeach station has grown even faster. Over the same period, entries and exists have grown by 316 per cent to 421,000.

Third, an argument can be made that the A10 is operating rationing by queue, pushing people into alternative journey and even lifestyle choices. There may be an element of truth in this, but upgrading the A10 between Ely and Cambridge to try and accommodate present and future demand would do little to solve congestion, and could conceivably make it worse.

Road building could never keep up with demand

Road building could not keep pace with Cambridge’s growth even if it was affordable and desirable to try.

Cambridge is a major economic and social centre. The population, already growing strongly, is now being supplemented by large new suburbs to the south and west of the city. Cambridge also serves a significant hinterland of towns and villages who look to it for shopping, leisure and other services. Population growth is strong here too with, for example, plans for 11,400 more houses in East Cambridgeshire and 6,500 from the redevelopment of Waterbeach Barracks. There are also many visitors to Cambridge with the historic centre helping to attract 5.3m tourist visits a year.

The city has one of the strongest jobs markets in the country spurred by a burgeoning hi-tech sector. In 2011, the ONS reported that 95,000 people work in Cambridge with over 12,000 new jobs created between between 2004 and 2013 alone. Of those employed in Cambridge, over half (54 per cent) travel in from elsewhere and of these nearly three-quarters (73 per cent – 51,000 people) drive.

Cambridge is already rated the 13th most congested place in the UK with peak hour road commuters spending 27 a year hours in traffic jams.

Attempting to accommodate this level of growth would be like digging a trench in a swamp – it will fill up as fast as you can shovel. Is it, therefore, a sensible policy to try?

New roads generate new traffic

Ironically, there is good evidence that spending money expanding the A10 could make actually make congestion worse. The notion of induced traffic states that the more you spend on a road, the busier it becomes. The impact of this long-known phenomena has recently been highlighted on UK examples.

A report produced for CPRE examined 86 major road schemes completed over the last 20 years. Using official data, it reveals that the new schemes attracted significantly more traffic than other roads, and that this worsened over time with traffic growth being up to 47 per cent higher on the new roads than than the average on existing roads.

Contrary to received orthodoxy, the research also found the large majority of new roads produced little or no economic benefit either. Despite claims made in advance about job creation, only one in four of the new roads was able to demonstrate any new employment being created. This is an important finding with local authorities adjacent to Cambridge looking for ways to cash in on the success of their neighbour.

Damaging the crown jewels

Making the A10 bigger might have impacts beyond local congestion, too.

The success of Cambridge is increasingly significant to the UK economy. Along with a few other fast-growing cities, the Government is pinning its hopes on Cambridge to continue its growth and has announced a string of major investments and new powers to help make it a reality. Not only are proposals for an upgrade of the A10 not included in these plans, such a project runs counter to many of their objectives.

Big money is going into Cambridge’s infrastructure. A new section of the A14 is being constructed at a cost of £1.5bn. A further £500m is being spent through the 15-year city deal agreement with initial projects including bus priority on key routes, improved cycling facilities, and long distance foot and cycle paths stretching at far as Haverhill and Royston,

The rail network is being expanded significantly. A new station at Cambridge North is nearing completion, and Cambridge South and Soham are also expected to get the go-ahead. East-West Rail will reconnect Cambridge to Oxford via a new line, plans to reconnect Wisbech to the rail network are being considered and a project aiming to resolve strategic capacity problems north of Ely has recently got the go ahead.

A new combined authority for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough will soon elect its first mayor. Among the devolution deal’s new powers will be more control over buses, allowing the authority to plan services and fares strategically for the first time in 30 years.

None of this fits with spending millions trying to funnel more cars down the A10 into Cambridge.

What we should be doing instead

So, if trying to build our way out of road congestion isn’t going to work, what should we be doing instead? Rather than looking at congestion on the A10 and deciding more road is the answer, we should start by looking at the beginning and end point of journeys along the corridor and identifying the best way of meeting it. That is likely to include the following:

Better public transport – Bus use in Cambridgeshire has fallen in recent years because of reduced local government support and service cuts. This is typified by bus and coach traffic on the Cambridge – Ely section of the A10 falling by nearly a fifth since 2000. There is good reason to believe that this is about to change. Cambridge is pinning its congestion-busting hopes largely on buses. The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough devolution deal and the soon to be passed Bus Services Act offer an excellent opportunity to create a more integrated public transport network with more frequent services, newer, cleaner vehicles, shorter journey times, prioritised road space and better value ticketing.

Work is already in hand to improve the rail network with more stations and better services. As this is delivered, we can expect to see rail continue to take market share from road locally. Making train stations transport hubs served by local bus services would help, too, and reduce the isolation of villages like Wicken which despite being located on an A-road is currently served by only one bus a week.

An essential step in making public transport more effective will be improving ticketing. Better value fares that can be used across bus, train and hire bikes will tempt more people to leave the car at home, as they have in and around other cities. The Ely – Cambridge corridor needs to be part of this.

Better land-use planning – with more major housing growth planned, it is essential that new development is planned in a way that gives people genuine transport choice. Distant estates out of walking distance of shops and not served by public transport just condemn people to a life of sitting in traffic jams. We have to do better.

Walking and cycling – Cycling is part of the transport culture of Cambridge and the city is making overdue investment in infrastructure to support it. Decent quality cycle routes are also on the way linking Cambridge with Royston and Haverhill. While fewer would choose to regularly cycle from Ely to Cambridge, investing in better and safer cycling and walking facilities in and around towns like Ely would encourage more people to travel this way and reduce the number of short distance journeys taken by road.

Light good vehicles – Since 2000, vans have accounted for half the traffic growth between Ely and Cambridge. Driven by the massive expansion in home deliveries, taking measures to limit this sector could be an effective way of addressing congestion. Encouraging more deliveries off-peak, encouraging more combined operations and even the potential for some parcel rail freight supported by ‘last mile’ road delivery all present opportunities.

The A10 is not a great road – there are certainly things we can do to make it safer. But even on its busiest stretches, simply adding more lanes will not solve congestion. Instead, there are numerous other measures we can take to make our journeys better and which won’t condemn us to a lifetime sitting in jams. These are the things we should be campaigning for.

One thought on “Digging a trench in a swamp – Why widening the A10 won’t tackle congestion”